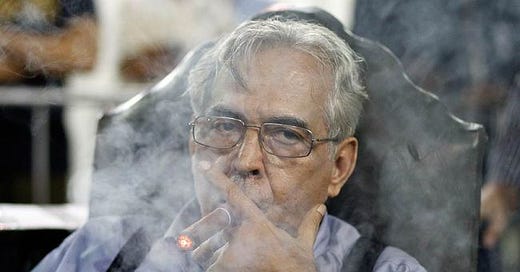

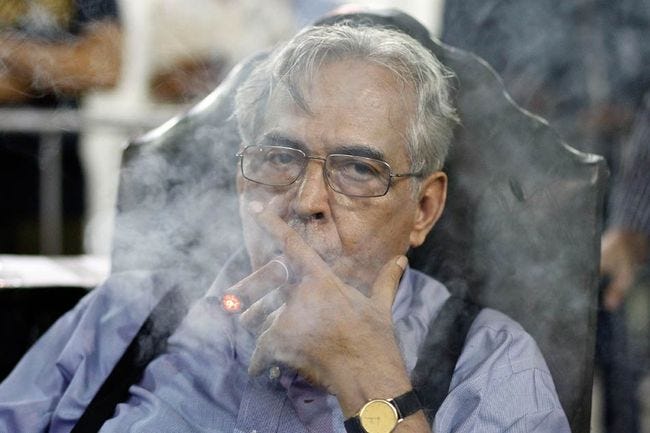

In the annals of Brazilian football, few figures have loomed as large—or as unapologetically—as Eurico Miranda. To call him just a sports executive would be like calling a hurricane just a bit of bad weather. Eurico wasn’t a man. He was an event. The kind of man whose entrance could change the temperature of a room and whose name alone could spark either a fistfight or a standing ovation. For Vasco da Gama supporters, he was a patriarch, gladiator, priest, and lightning rod—all in one chain-smoking, sharp-tongued package. For detractors, he was football’s pantomime villain: the cigar-chomping boss who wielded power with the subtlety of a sledgehammer and the diplomacy of a Molotov cocktail. Love him or loathe him, you never ignored Eurico Miranda. You couldn’t.

He was born in Rio de Janeiro in 1944—though, had you asked him, he might have claimed to be born directly in the bowels of São Januário, already wrapped in Vasco’s flag. He grew up in a city where football wasn’t just a pastime—it was politics, identity, mythology. And Vasco da Gama was no ordinary club. It was the club of inclusion, the first to embrace Black and working-class players, the one that fought the power and built its own stadium rather than bend the knee. In that sense, Vasco wasn’t just a club—it was a cause. And Eurico, ever the political animal, was destined to be its most fervent crusader.

By the 1970s, he’d elbowed his way into the club’s boardroom, already puffed up with the mix of bravado and belligerence that would define his reign. He wasn’t there to be liked, or even tolerated. He was there to conquer. In his view, football was no place for softness, and diplomacy was often just cowardice in a necktie. From that moment on, Eurico Miranda began his transformation from director to deity—reigning over Vasco with an iron fist, a steel jaw, and the moral flexibility of a street fighter who just wanted to win.

And win he did—though not without casualties. Eurico’s rise coincided with Vasco’s golden age, a period that saw the club crowned champions of Brazil and even of South America. He was the dark architect behind the 1998 Copa Libertadores win, orchestrating deals, moving pieces, and placing pressure on every lever of power he could reach. To his credit—or to his notoriety—he saw the whole chessboard. He wasn’t just running a football club; he was managing a war campaign. Transfers were maneuvers. Press conferences were battlefields. The football federation? An enemy camp to be infiltrated or blown up. And Eurico never missed an opportunity to strike.

But where most men of power operate from the shadows, Eurico basked in the spotlight. He didn’t just tolerate attention; he demanded it. Whether he was shouting down TV pundits, berating referees, or barging into rival locker rooms, he performed his power. Theatrics weren’t a flaw in his game—they were the game. He made himself inseparable from Vasco’s identity, to the point where one couldn’t tell whether the club was his stage or his hostage. When he returned to the presidency in 2014 after a brief hiatus, it wasn’t out of necessity—it was out of compulsion. Like a retired general bored by peace, Eurico couldn’t help but come back to the battlefield.

One of his most infamous wars was the São Januário affair in 2000. At stake was more than just a venue for the Brazilian championship decider—it was a statement about loyalty, sovereignty, and the refusal to be intimidated by corporate convenience or institutional pressure. While broadcasters and organisers lobbied for the final match to be held at the Maracanã, Eurico stood his ground. São Januário was sacred. It was more than bricks and bleachers—it was Vasco’s beating heart, built by its fans when no one else would accept them. For Eurico, compromising on that was sacrilege. He planted his flag, lit his cigar, and dared anyone to move him. No one did.

But the cost of perpetual war is high. Eurico’s legacy, much like the man himself, is deeply polarising. Behind the trophies and triumphs lies a long trail of accusations—of corruption, financial mismanagement, authoritarianism, and mafia-style governance. Transparency was not in his vocabulary. Critics often compared his rule to that of a South American caudillo—more interested in loyalty than legality, more focused on power than process. The club's finances suffered, the institutional structure crumbled, and Vasco entered a prolonged period of instability, oscillating between flashes of resurgence and deep-rooted crisis. The same strong hand that built glories had also tightened into a chokehold.

And yet, to reduce Eurico to a villainous caricature would be both too easy and too lazy. Because here’s the inconvenient truth: for a generation of Vasco fans, Eurico was not just a necessary evil—he was their champion. They didn’t love him despite his flaws; they loved him because of them. He was defiant in the face of ridicule, unbowed by power, and fearless in defence of a club that has always prided itself on standing apart. In a footballing world increasingly sanitised by corporate suits and sterile executives, Eurico was gloriously, infuriatingly human. He had a pulse, a temper, and a purpose. And above all, he had presence.

There was something almost operatic in the way he ruled—larger-than-life, absurd, tragic, magnificent. He was football’s Don Corleone crossed with Don Quixote: always in control, yet often tilting at windmills of his own imagination. His obsession with control was also his fatal flaw. He could never delegate, never let go, never imagine Vasco existing outside his shadow. That, more than any scandal, is what ultimately undid him. His era ended not with a bang, but with a long, reluctant decline—a warrior without a war, a general left pacing a peacetime palace.

Eurico Miranda died in 2019, and with him went one of the last great avatars of the old Brazilian football—unpolished, impassioned, and utterly incapable of compromise. His passing was met with both mourning and relief, depending on where you stood. For some, it was the end of an era drenched in passion, trophies, and defiance. For others, it was a long-awaited exorcism. But whichever side you fell on, one fact remained undeniable: no one could replace him. No one would dare try.

In the years since, Vasco da Gama has tried to navigate the new world—one of SAFs, investor boards, rebranding, and performance analytics. But the ghost of Eurico still lingers in the corridors of São Januário, like the stubborn smell of cigar smoke in an old boardroom: intrusive, unmistakable, and oddly comforting. Because Eurico, for all his flaws, was real. He bled the club’s colours. He fought its battles. And he did it all with the conviction—no, the delusion—that he was the club.

There will never be another Eurico Miranda. And that may be a blessing. But it is also, in some inexplicable way, a loss. For football is poorer without men like him—men too big for their suits, too loud for their microphones, and too proud to ever say sorry. He was the maverick king of São Januário, and whether he left the club better or worse is still up for debate. What’s not is this: he never left it indifferent.